Unbound 200

Racing 200 miles, on gravel roads to learn about doing hard things

At the end of May, I did the hardest physical feat of my life. I rode 200 miles straight, on my bike, on gravel roads in Kansas. This was part of a cycling event called Unbound, the premier race of gravel cycling worldwide. Thousands of people, from hundreds of countries, converge on rural Emporia, Kansas to test their endurance against the dusty hard-pack roads and sweltering heat.

Route & Race Overview

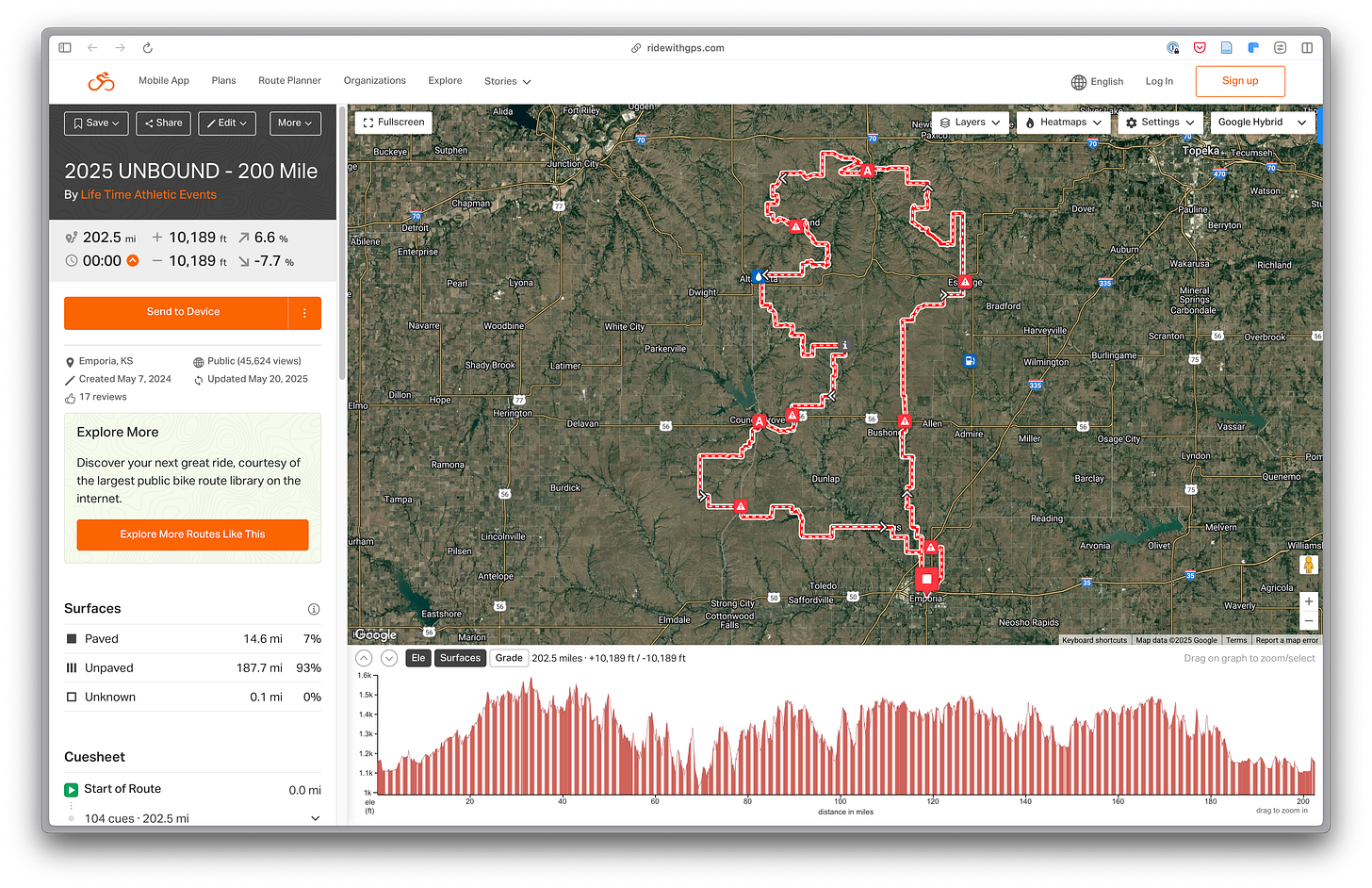

Unbound alternates between two courses every two years. This year's course was the northern route, known for being faster, less muddy, but as a consequence of the flinty gravel, more prone to flats. The route is just over two hundred miles and consists of 90% gravel roads that connect dispersed towns around Emporia, like Alma, and Council Grove. Though many sections are flat and straight, prioritizing aerodynamics over power, over two hundred miles, you accumulate over ten thousand feet of elevation gain.

Race

Now that the race is finished, now that I am recounting this, it’s hard to imagine that it ever felt so hard, or at least hard enough that I wanted to quit. But, there was a fifty mile stretch where my mind could not comprehend going any further. I could not imagine making it another 10 miles, let alone another 130.

In cycling, and particularly in races like Unbound without any substantial climbs, it’s important to stick with a group as much as possible. Forming a group of riders allows you to work together, taking turns breaking the wind for the other riders. Favorable aerodynamics let the group reach a much higher average speed than an individual riding alone.

At 6:30am, shaking off nerves from the start line, we hit the gravel roads in a massive group of more than one thousand riders. In a group like this, things are a blur. Your vision is narrow. The dust blocking out any scenery. Your brain is fully utilized on the tasks of avoiding crashes and staying towards the front. At each turn, your tires’ grip is tested in the midst of a mini-traffic jam as riders slow from back to front to make the corner safely.

There were a few sporadic crashes in front of me that thinned out the stampede, but I was able to avoid any pile ups. My legs felt great and I was locked-in on the pack when I was suddenly snapped out of the trance. The shifting on my bike was not working. For the non familiar, let me explain how that’s possible: I have electronic shifting, where instead of the typical mechanical cable from my handlebars to the derailleur, an electronic signal tells the derailleur when to change gears. Something had happened to my battery that rendered my shifting non-existent. It hand’t crossed my mind, but suddenly, in the throng of tightly clad two-wheeled racers, I was hyper aware of the lack of redundancy and fault-tolerance of my bike’s design.

Honestly, I was more freaked out that the battery was dead and not loose. I had replaced it the night before with, what I thought was a freshly charged battery. Spinning on the doomsday scenario of an unforced error, my mind spiraled through all the preparation, months of training and anticipation, and how one silly mistake might cost me the chance to complete the race. From where I was, I wouldn’t be able to replace the battery for another fifty miles. If it was only lose and not dead, it should be a quick fix, less than 30 seconds; however, with aerodynamics and the speed of the group, thirty seconds is a lot of time, so I continued to ride without shifting, fighting for my position in the group.

On a short uphill, my legs began to feel heavy with the disadvantageous gear ratio and I quickly realized I wouldn’t be able to keep up with a single speed. I needed my shifting to continue. I pulled over to the side of the road, the swarm of riders whizzing by, hemorrhaging positions by the seconds. Quickly, my shifting was back, but at the same speed, I faded mentally.

In the minutes of the race where I contemplated the defeat of a dead battery, I had spread a virus in my mind. Even though my bike was working now, pulling over had cost me the front of the group and I would have to push myself to try and catch back. Immediately, a stressful calculus came into play. If I dug too deep to get back, I’d risk blowing up and not finishing the race, failing the singular goal I’d spent months preparing for. But if I took it too chill, I’d lose the group, ride alone in the wind for a little longer than planned. Reframing my goals to focus solely on salvaging my position and completing the race, I aimed for a steady effort in the middle. But even a steady effort proved difficult.

During this middle section slog, there was no part of my body that wanted to continue. I was sinking. Groups of four or five riders would come smoothly riding past as I fought to turn over the pedals. Normally, I’d be able to catch on, but I felt zapped. I was counting down the miles and time, trying to reach little self-fabricated checkpoints to feel a little sense of achievement. “Ok, if I can make it another five miles, I can stop in the shade for a minute.” “Maybe just another ten minutes.” I hoped an accumulation of these mini-wins would turn my day around.

At mile 112, I stopped at the race provided aid station to refill bottles, douse myself with ice water, and pace around. At this point, the mind virus had not been exorcised—I was still contemplating how I could continue and how long it might take if I did. I had spent the last couple of hours solo, but there didn't seem to be another option, so I picked up my bike and headed out alone, again. This time however, within a couple of miles, a group of 4 riders relaxed their pace enough for me to latch on and join their rotation. We worked together for 5 miles, my confidence trickling back.

Almost as quickly as my mind had snapped at mile 30, my psyche started to rebuild itself. Feeling a strong differential between how I had felt and how I was now feeling, I began to believe that I would finish the race. With this, I started to feel my legs less; I felt like I was moving faster, slowly reviving myself. In a short time, I started to ride away from the group I was with, realizing that I was feeling much more than the rest of them. Slowly but steadily, I started to make up positions and time, catching other groups and subsequently dropping them. Over the last half of the race, I made up almost one hundred positions. It really all is in your head.

Mental battles like this never fail to remind me of a theory of endurance called the “central governor”1. The central governor theory proposes that the brain regulates exercise performance by subconsciously limiting muscle activation. This helps prevent physiological harm, but can also set unhelpful limits that, with the right tactics, can be pushed past. The strength of this theory is apparent to any endurance athlete, but for a more nuanced take, you should read Alex Hutchinson’s book, Endure.

Would I do it again? Unlikely. The race served its purpose as a months long goal to push myself with a singular pursuit. I find myself chasing these achievements with a chip on my shoulder. As a very logical thinker, it’s helpful to have these solidified, metric-based achievements to look back on. At the end of the day, it’s about two of my core values: endurance and challenge. I’m building my ability to keep my hand in the fire, to do things that I don’t want to do, and to have a little bit of fun in the process.

Appendix

Training Structure

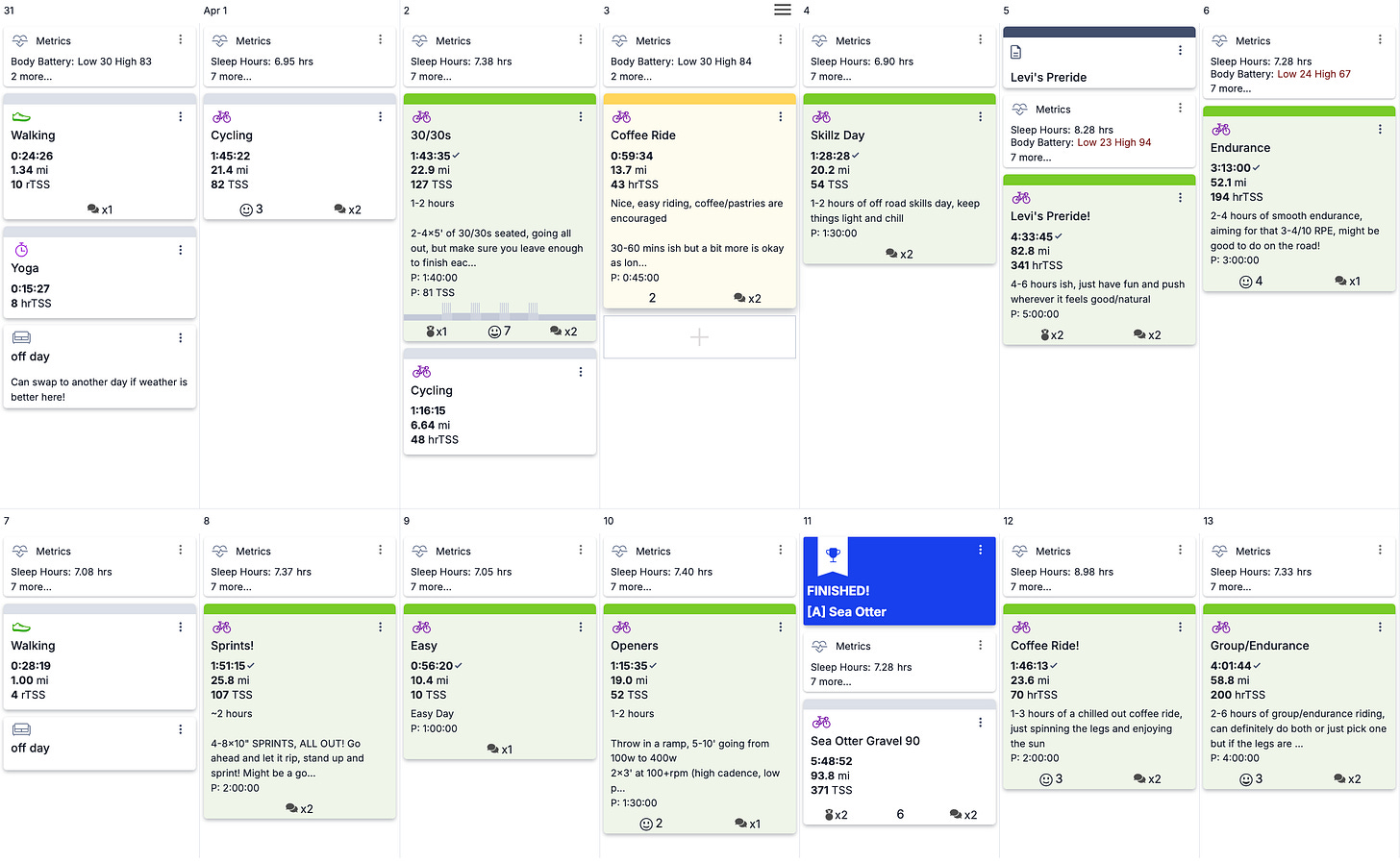

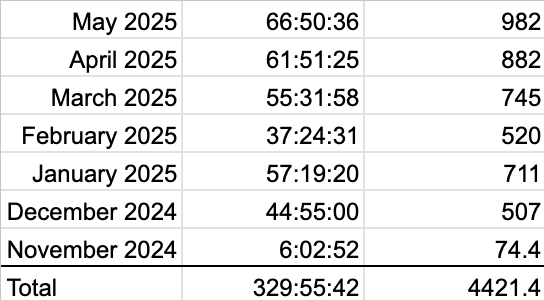

In November, I got a spot at Unbound, through the lottery system, and made the quick decision to contract with a coach to structure my training (shoutout Katie Aman!). Since November, I have been spending the majority of my free-time preparing for this race. The preparation consisted of training-weeks between 10 and 15 hours long. The training consisted of a polarized method where the majority of the volume is low intensity, mixing in one to two interval sessions throughout the week.

To account for this volume while working full time, I often wielded my Saturday for a long ride or woke up at 5:30am for an interval workout. Some weeks were much easier than others and training would go off without a hitch, but others just felt off. There are too many variables (e.g., sleep, stress, timing, etc.) that it was hard to tell precisely what affected each week, but working with a coach helped add accountability and a outside perspective. The metric-based nature of training is both a blessing and a curse: it’s easy to see improvements, but it can get in your head when the numbers don’t line up with how your body feels. On top of regular training, I participated in many races, road and gravel, in the months since January.

Race Day Fueling

I devised a fueling plan that included both gels and a carbohydrate drink mix. The recommended consumption ratio is between 60g to 90g/h. I had been doing 90g/h during training rides and had practiced 120g/h on a few rides before Unbound. I was aware that fueling throughout the entire day was going to be a struggle and I would likely have to swap out for solid food and normal water as the heat wore on and my stomach’s ability to convert the inputs to energy began to fade.

My fueling plan was ambitious. My target consumption was around 120g/h, 80g from gels and 40g from my drink mix. I carried about 4 hours worth of gels in my jersey and wore a bladder pack on my back with the drink mix. On top of that, I filled my bike bottles with normal water to wash the sugar down and eventually dump down my back when it was hot.

My approach was far from the most ambitious, Cam Jones reported consuming 195g of carbohydrates an hour. Insane!

Official Result

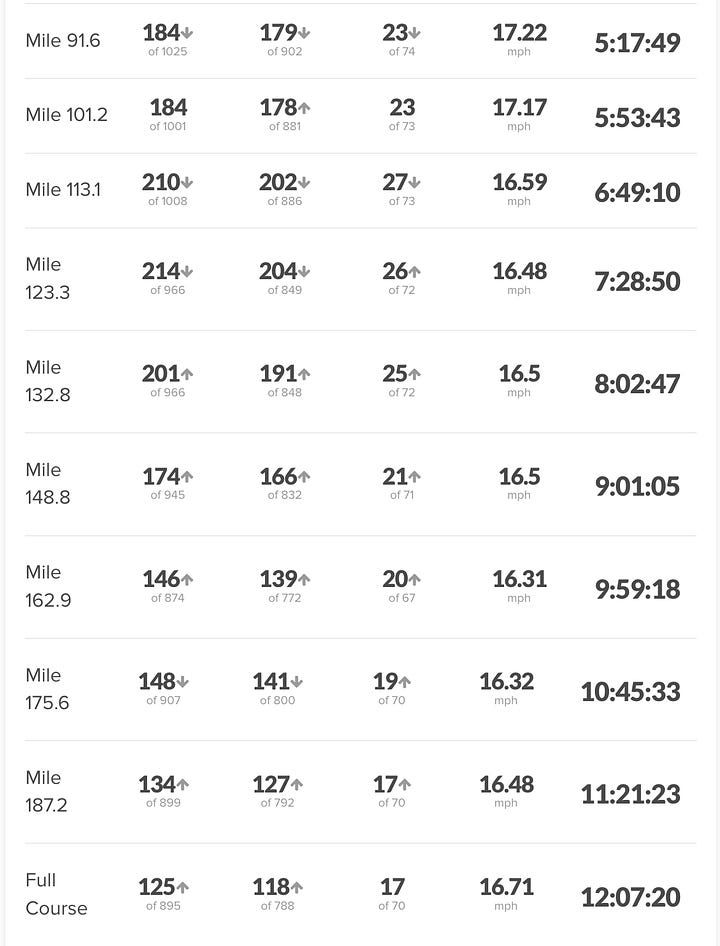

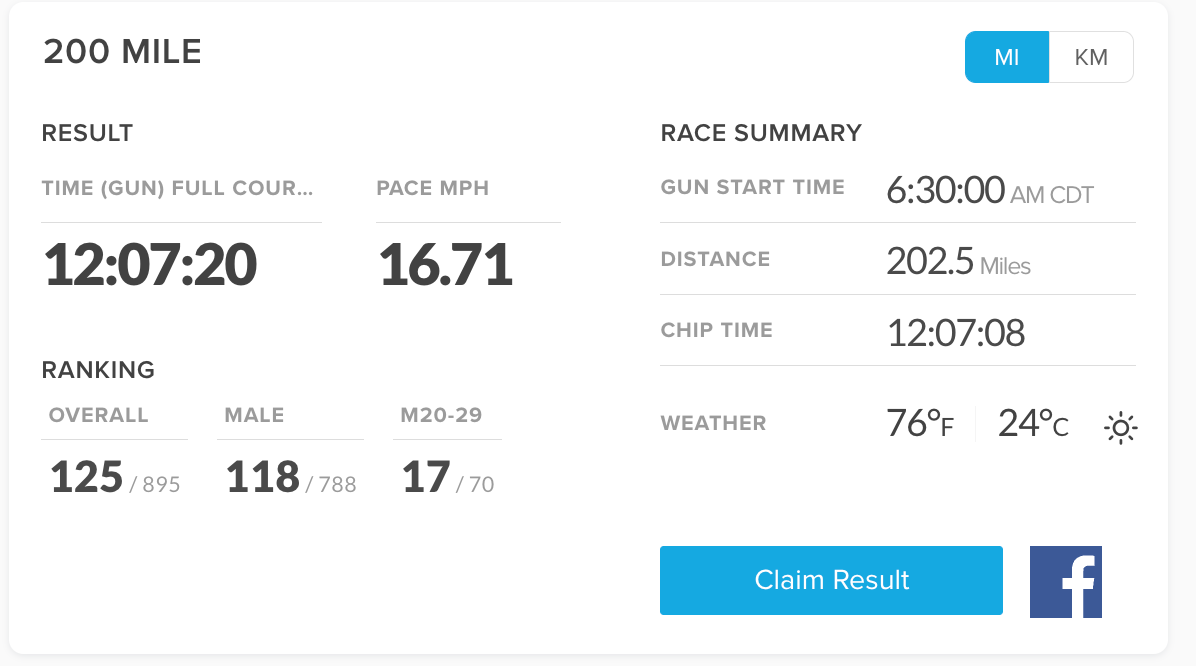

Finish Time: 12h:07m:08s

Placing: 125/895

Average Speed: 16.71mph

Average HR: 148 bpm

The mere completion of this race was a challenging feat for me and certainly something I take pride in; yet, there is an incredible amount of people that did this faster than me. Hundreds of Elite (pro) riders took on the course ahead of me with the male winner, Cam Jones, finishing in just under eight and a half hours and the female winner, Karolina Migon, finishing in ten hours and three minutes. You can do the math: both averaged over 20 miles per hour!

Unbound is a race that has been going on for years and there is abundant content from the professionals on YouTube. If you want to continue your rabbit hole, here is the recap of the professional race from this year:

I hope you get to explore this niche sport because this is how I discovered Unbound, a few years ago, and appended it to my growing bucket list.

impressive!!